Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the School of Applied Arts in Basel had become a crucible of creativity, with a reputation that extended to the United States and India. Its leaders, concerned with formal rigor, provided education that was in line with the tradition of Walter Gropius’s Bauhaus. René Mayer fully benefited from these unconventional courses…

The sources of inspiration

When asked “What educates and instructs?” (“Was bildet?”), the great German educator Hartmut von Hentig responded “Everything!” (“Alles bildet!”). The elegant simplicity of this answer is disconcerting for two reasons. First, it bluntly dismisses any elitist tendencies by clearly stating that everything, yes everything, including trivial matters, educates and instructs! Second, it reminds us that there isn’t just one, but a myriad of ways to educate oneself. Various concepts of education and instruction are offered by the countless cultures that shape the being and becoming of civilization – the face of humanity. Educating and instructing, therefore, is not simply about pouring knowledge onto more or less motivated ignorants, but about encouraging them to look instead of just seeing, to listen instead of merely hearing, to become actors instead of remaining spectators of life – their own and that of others. In short, it’s about taking action.

Some may wonder if von Hentig is subtly suggesting that ultimately, and barring exceptions, we are merely the subject, object, and result of the social, cultural, economic, and political currents that condition the world and to which we more or less (un)consciously submit. Is the educator not implying that these currents practically shape our character and behavior without our knowledge? – Certainly not, because that would amount to denying free will, personal initiative, and individual responsibility. Thus, it would say exactly the opposite of what von Hentig intended to convey.

Choosing one’s path

Affirming that everything educates and instructs is a challenge to the reason and will of each individual: “See: I provide you with everything necessary for the formation of your mind, the development of your intelligence, and the blossoming of your creativity. It is now up to you to choose your path and move forward, with the means at your disposal and the instruments that I offer you! It is your responsibility and it will be your honor.”

Of course, no one delivered this pompous and stiff speech to young René Mayer when he was searching for his path. And he himself, pragmatic as he is, would never have dissected, analyzed, and summarized his situation in this way…! But the fact is that he, like all of us, experienced episodes of apprehension, uncertainty, and doubt in his family and social environment as well as in his academic and professional journey. Moments when he questioned the relevance of his choices, the validity of his skills, the reliability of his feelings. And later on, the meaning and quality of his art. However, these moments – which for others would be occasions for rupture or near-rupture – never broke him. Quite the contrary: they galvanized him! Because without being expressly aware of it, he lived according to Friedrich Nietzsche’s famous formula: “Was mich nicht umbringt, macht mich stärker” (“What doesn’t kill me makes me stronger”). His strategy? Take control of the situation, apprehend the problem, overcome the obstacles, bounce back – and win! QED.

With maturity, René Mayer did not slow down to retire into the cushy and frivolous inconsistency of a golden retirement. Drawing on his life experience, he continued (and still continues) his human and artistic quest, approaching with permanent enthusiasm, unshaken confidence, and unwavering optimism the challenges that line his path. Isn’t one of his favorite mottos “Passion never retires!”

Taking one’s bearings

When setting a goal, it is just as important to know one’s starting point as it is to know where one wants to end up. Because there is a route to define, and it requires clear landmarks. Yet, many people embark on the ocean of life with the ambition to cross it gloriously but, for lack of setting themselves the necessary landmarks (and often also the instruments), find themselves swaying and rolling in the open sea in boats without oars, without a rudder, without a compass, and without protection against the vicissitudes of the weather…!

Accustomed since childhood to being vigilant and relying only on himself, René Mayer developed in his youth a humanistic pragmatism based on an empirical and positive, but not illusionary, conception of the world. This realism is accompanied by a clear perception of obstacles and dangers. Of course, this does not imply that he is pusillanimous. On the contrary: being of a daring temperament, he has always considered risk as a stimulating, energizing element. So, when René Mayer decided to enter the art world, he did not simply throw himself blindly into the unknown. He took a calculated risk – and somewhat contracted a risk insurance by founding a small company dedicated to the arts of the table, whose income would provide him with the financial security required to devote himself serenely to his artistic experiments. The concept worked perfectly. Thanks to his ever-vigilant insight, his infectious enthusiasm, and his ability to anticipate trends, but also (if not especially!) thanks to the very foresighted administrative and financial management of Karin Bosshardt – the professional partner with whom he founded Mayer & Bosshardt in the 1970s – the company established itself among the market leaders in just a few years. It became a public limited company in 1990, under the name Mayer & Bosshardt AG.

Multiple sources of inspiration – and contradictory ones?

It all began in the 1960s when René Mayer enrolled in the preparatory course at the School of Applied Arts in Basel (now the School of Design). The preparatory course is a propaedeutic course for students from secondary levels I and II who wish to study in the fields of art and design. It provides future students with the necessary knowledge to successfully enter the professional classes of art and design schools.

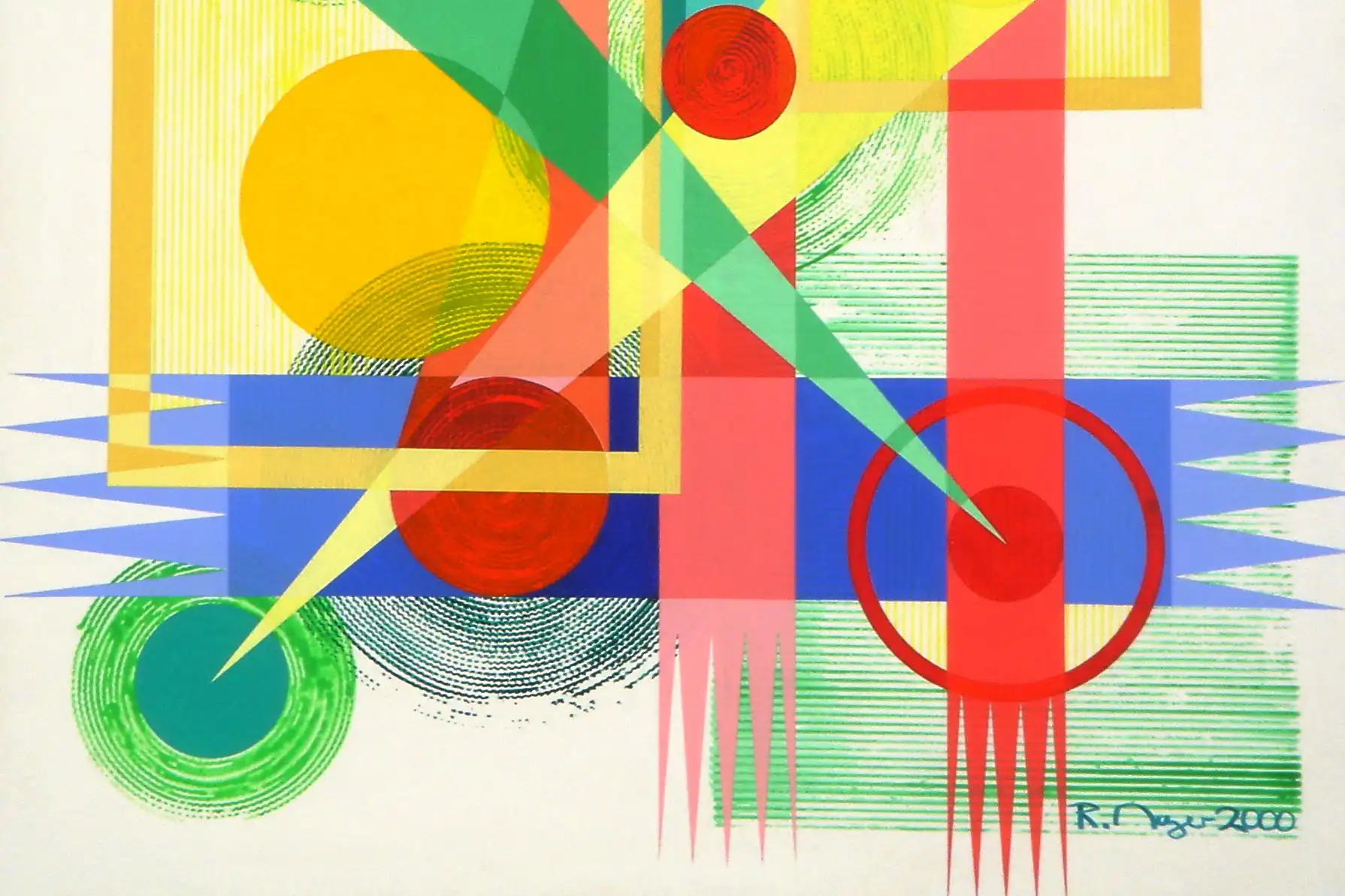

The teaching at the School of Applied Arts was a real catalyst for René Mayer’s creativity. It was in the classes and practical work at the school that he discovered everything that would soon mark his art, starting with the color theory of the Swiss painter and teacher Johannes Itten (1888-1967), whose color circle is famous worldwide. Color theories describe the psychological effect of colors on humans and explain how to master colors in artistic and graphic creation. There are many versions, by authors as diverse as Isaac Newton, Wolfgang von Goethe, Wassily Kandinsky, or Robert Delaunay. But it was Johannes Itten’s theory that impressed René Mayer the most. Itten’s goal, who was a “master” (that was the title given to teachers) at the Bauhaus in Weimar from 1919 to 1923, was to liberate creativity and develop the craft skills of students. René Mayer, for whom art and craftsmanship go hand in hand, still emphasizes today the importance this teaching had on his artistic development. Johannes Itten ended his career as the director of the School of Applied Arts, the Museum of Applied Arts, and the Textile Vocational School in Zurich.

Throughout the preparatory course, René Mayer noticed that only four or five of his classmates were fully invested. Quickly identified by the teachers, this small group was strongly encouraged by them. The help of the teachers can be explained, firstly, by the fact that they were artists themselves, and secondly, by the school’s desire to stimulate creativity in all its forms, in order to maintain its hard-won pioneering reputation. These teachers followed the example and injunction of Joseph Beuys (1921-1986), who encouraged his peers to engage in teaching. Beuys, a German conceptual artist, member of the Fluxus movement, and professor at the Düsseldorf Academy of Fine Arts, initiated a revolution in art pedagogy in the 1960s. On one hand, he welcomed anyone wishing to devote themselves to art into his classes, even if they did not have the officially required qualifications, and on the other hand, he encouraged artists to engage personally in art education, in accordance with his famous formula: “Lehrer zu sein ist mein grösstes Kunstwerk” (“To be a teacher is my greatest artwork”).

Austrian sculptor Alfred Gruber (1931-1972) was one of those teachers inspired by Beuys. He emigrated to Switzerland in 1955 and settled in Dittingen, in the canton of Basel-Landschaft, with his wife – also an artist – Jacqueline Gruber, nee Stieger. Alfred Gruber taught at the School of Applied Arts (now the School of Design) in Basel from 1963 onwards. When the Gruber couple left Dittingen for Great Britain in 1972, they handed over their house and studio to another immigrant artist: the Czech Čeněk Pražák.

Alfred Gruber collaborated with Swiss sculptor Albert Schilling (1904-1987) and with Hans Arp, also known as Jean Arp (1886-1966), internationally renowned for his sculptures with organic forms. Alongside his wife Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889-1943), Jean Arp participated in the Dada and Surrealist movements. The Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Strasbourg owns numerous works by him.

A motivated and atypical teacher, Alfred Gruber often welcomed disciples into the workshop he had built with their help in the heart of the abandoned Schachental quarry on weekends. A workshop where passionate discussions took place, experiments were carried out frenetically… and joyful celebrations were held!

The Bauhaus and its two poles: craftsmanship and industry

Besides the generic education received at the School of Arts and Crafts in Basel, it is undoubtedly the legacy of the Bauhaus, as verbalized or materialized in the color theory of Johannes Itten, in the design of chairs by Marcel Breuer, in the architectural principles of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and in the rationality of everyday objects or the rigor of artworks by other Bauhaus protagonists, that has deeply influenced René Mayer.

A small anecdote about Marcel Breuer, who was a student and later a teacher at the Bauhaus. He is the father of the famous B3 “Wassily” chair, so named because it is said to have been created for Wassily Kandinsky, who dreamed of a Chesterfield armchair. Chesterfield armchairs are massive and heavy English leather seats. The B3 has the dimensions of a Chesterfield, but it is ultra-lightweight, being constructed of tubular steel with a leather seat, backrest, and armrests. Breuer allegedly gave a B3 to Kandinsky, saying, “Here is your Chesterfield. I just removed everything that characterizes the Chesterfield!”. Se non è vero è ben trovato…

The Bauhaus was a school of architecture and applied arts founded in 1919 in Weimar by architect Walter Gropius. The institution was relocated in 1925 to its iconic building in Dessau and finally exiled in 1932 to Berlin-Steglitz. Its last director, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, closed it in 1933 under pressure from the Nazi authorities, who suspected it of being a hotbed of Bolshevism and “degenerate art.” The Bauhaus’s activities revolved around two credos that strongly influenced René Mayer. One, formulated by Walter Gropius in 1919, stated: “The goal of all artistic activity is the construction! […] Architects, sculptors, painters, we must all return to craftsmanship!”. This desire to revalue the applied arts, then considered minor arts without the splendor, nobility, and prestige of fine arts, perfectly resonates with René Mayer’s character, who still affirms today that he is at heart a craftsman.

The second major maxim of the Bauhaus was also formulated by Walter Gropius, but in 1923. It marked the academy’s conversion to industrial styling (now called “design”), a discipline that was still in its infancy and to which mass production – which was increasingly voracious and shamelessly devouring trades hitherto considered the prerogative of craftsmanship – promised a bright future. Walter Gropius’s new credo: “Art and technology – a new unity” (“Kunst und Technik – eine neue Einheit”). It is from this maxim that the simple, streamlined geometric forms characteristic of what is sometimes called the “Bauhaus style” emerged. It is in this perspective, among others, that one must understand his interest in artists such as Oskar Schlemmer, Kandinsky, Lyonel Feininger, or Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, all of whom passed through the Bauhaus.

The fascination with organic architecture

But René Mayer is not only a proponent of geometric rigor. In contrast to his attraction to the combination of technique and design, he also appreciates the organic, biomorphic side of anthroposophical architecture as implemented by Rudolf Steiner in the Goetheanum (the headquarters of the anthroposophical movement, named in honor of Goethe’s scientific works, which Steiner admired). The Goetheanum, located in Dornach, about ten kilometers from Basel, is surrounded by villas built in the same style. René Mayer does not share Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophical doctrine, but he was fascinated by the unique architectural concept of the “anthroposophical quarter” of Dornach. This fascination grew stronger when he saw how consistently the individuals living and working in these buildings devoted their leisure time to art. Anthroposophical architecture is part of the organic architecture movement initiated in the early 20th century in the United States by the great architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright’s goal was to put architecture in the service of a holistic vision of life – to promote an architecture in which art, science, and spirituality blend into a harmony of form and function to create a “total work of art.”

From theory to practice

After his time at the School of Arts and Crafts in Basel, René Mayer sought employment that would allow him to deepen his understanding of the art-craft duo. He thus got in touch with Hans Hinz (1913-2008), a renowned specialist in art photography. In his Basel studio, Hinz trained around twenty young individuals in this complex technique. René Mayer was one of them. In this capacity, he assisted Hinz in photography sessions at renowned museums such as the Prado Museum in Madrid – where they had to work at night, after the museum closed (waiting for the departure of the last visitor to set up projectors and a professional photographic chamber), under the supervision of security guards who ensured that they did not cause any damage or commit theft…! This experience made René Mayer aware of the complexity of classical masterpieces – the rigor and skill of their conception, as well as the richness and subtlety of their colors. Mayer’s vocabulary was enriched with new words – new concepts: colorimetry, density, luminance, chromatic balance. René Mayer discovered that a technically complex universe unfolded behind the scene depicted in the painting. At the same time, he familiarized himself with notions such as the structure of canvases, the physical composition of colors, the painter’s touch – and the physical evolution of the painting due to aging and pollution. He realized that photographing a painting by Velasquez or Goya was not at all the same as photographing a work by Tintoretto or Caravaggio. And that photographing Picasso or Braque’s cubist works was something else entirely…

This experience proved extremely useful when he joined as a photographer at a renowned Zurich advertising agency known for its creativity: “Werbeagentur Hans Looser”.

Conclusion

René Mayer’s sources of inspiration have been shaped by his youth apprenticeships and personal favorites. Naturally, over the years, these sources have multiplied and diversified. Today, René Mayer’s artistic and cultural horizon is much broader and deeper than it was fifty years ago – he is interested in figures as diverse as Nicola De Maria, Anselm Kiefer, Mark Rothko, and Valeri Adami, to name just a few randomly. However, he has remained faithful to the major directions he took at the beginning of his artistic career.