A long history – from vanishing point to erasure

In Western painting, linear perspective long served as the central tool for organizing visual space. Since Brunelleschi and Alberti, the canvas was conceived as a window into the world, built on one or several vanishing points. This system, perfected by Piero della Francesca, Leonardo da Vinci, or Mantegna, became the academic canon.

The cancellation of perspective emerges as a critical gesture. It is not a technical flaw, but a deliberate attempt to neutralize depth and restore the power of the plane. This refusal runs through the Cubists, who multiplied viewpoints to dismantle spatial coherence, Malevich and his geometric radicalism, the Russian Constructivists, and later Josef Albers and his frontal compositions.

In contemporary art, this strategy becomes conceptual: it is no longer about representing an external world, but questioning the conditions of visibility. The painting ceases to be illusion and becomes structure. The cancellation of perspective transforms painting into a field of experimentation, where seeing also means thinking.

A visual choice – not an automatic consequence

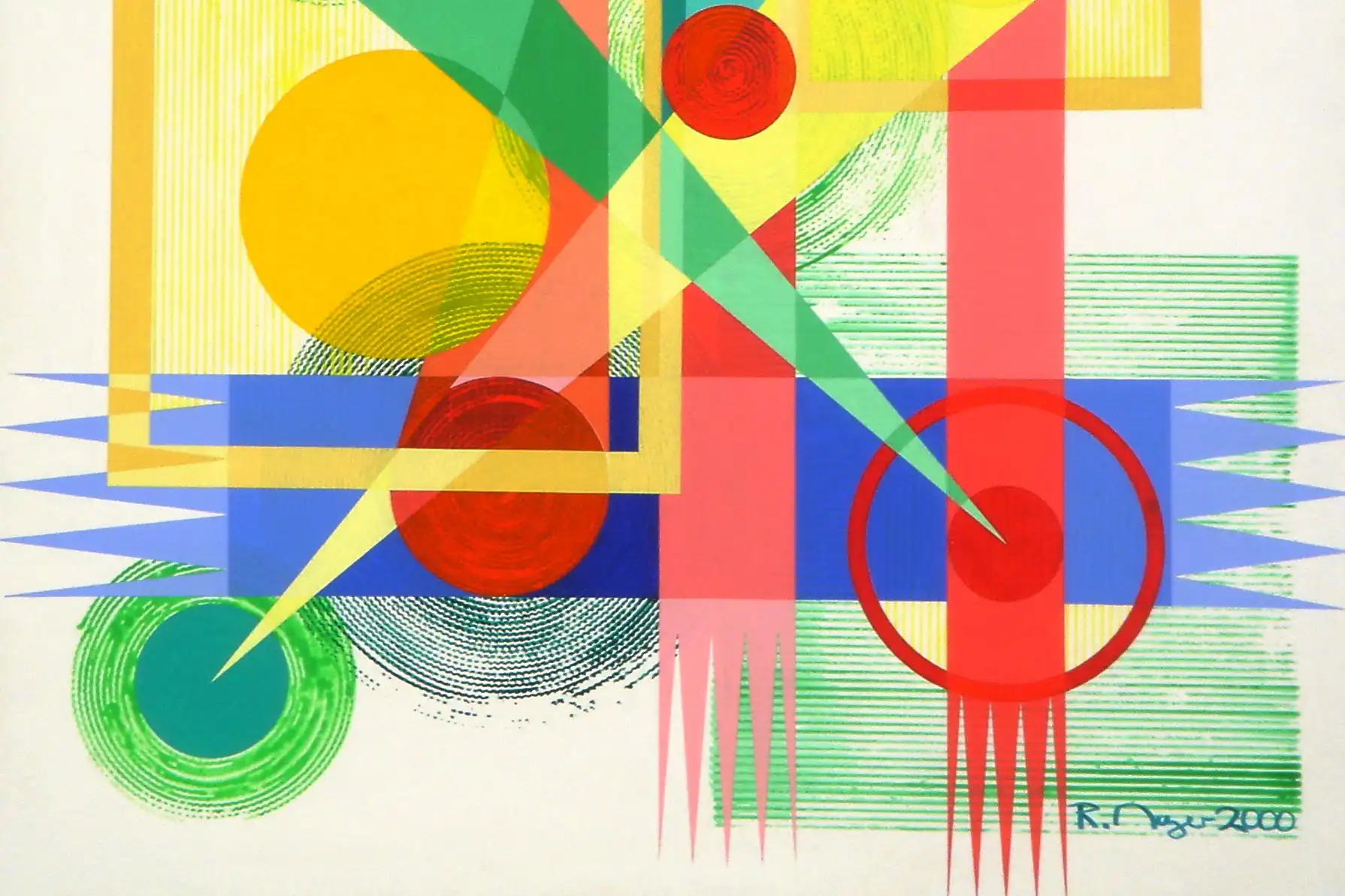

For René Mayer, the cancellation of perspective is a conscious decision. His works, even abstract ones, could suggest horizons or gradients, yet they consistently refuse any spatial cues. No center, no depth, no vanishing point: everything happens on the plane.

The pictorial surface becomes a site of action. This choice refutes illusionistic reading and forces us to consider the relationships between forms. Squares, circles, layers, or grids never arrange themselves in fictive depth: they coexist in rigorous frontality. The viewer does not enter the image but circulates across its surface. It is a way of rejecting the singular vision inherited from the Renaissance and replacing it with a shifting balance of visual tensions.

“Boxes” – the square as critical tension

The “Boxes” series illustrates this radical relationship to the plane. Grids and squares could suggest the illusion of a stable architectural space, but all depth dissolves. Nothing allows the gaze to escape: everything remains on the surface.

Here the square becomes ambivalent: protective cell or prison. This visual and symbolic ambiguity raises an ethical question: are we confined in order to be protected, or protected at the price of freedom? By refusing perspective, René Mayer radicalizes this tension. The spectator, unable to escape into a background, must confront the surface saturated with signs.

This choice echoes analyses close to Michel Foucault on disciplinary systems: the grid as diagram of power. Where Albers explored chromatic perception through squares, Mayer makes them a critical tool. The cancellation of perspective functions here as a visual weapon: it exposes structure instead of concealing it behind reassuring illusion.

“Moving Earth” – materiality without depth

In “Moving Earth”, René Mayer introduces a new material: crumpled, glued, worked paper. This relief does not imitate depth; it affirms instead an uneven surface. The material becomes a metaphor for a shaken earth, traversed by tensions.

Superimposed upon this organic surface are sharp geometric forms — triangles, squares, circles — that do not structure space or open depth; they wound the plane.

The result is a field of forces, without horizon or vanishing point, recalling Burri’s burned canvases or Smithson’s fragmented surfaces. Yet with Mayer, everything is orchestrated so the surface remains legible: the image is not illusion but active tension.

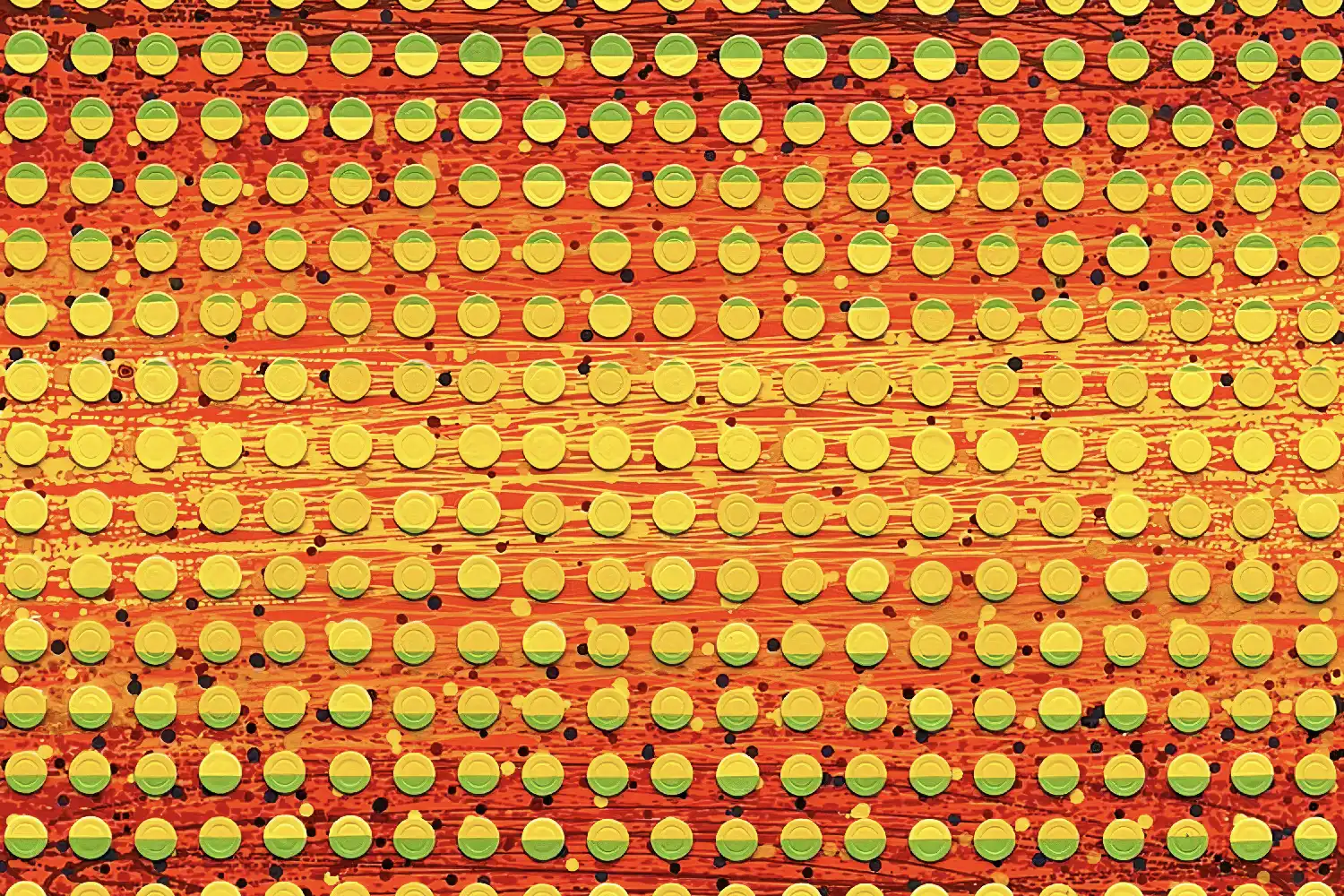

“Imperceptible Shift” – controlled chance, asserted plane

With “Imperceptible Shift”, René Mayer pushes this logic further. Casino tokens are repeated, aligned, dispersed with almost algorithmic rigor. But they never produce depth. Each token remains equidistant from the gaze: not nearer or farther, but placed on the same plane.

In some canvases, René Mayer experiments with a pendulum dispersing paint along unpredictable paths. Yet this randomness remains marginal: the essence of the series lies in the tension between the geometric rigor of the grid and the instability introduced by the colored tokens. Chance intervenes as disturbance, not as absolute principle.

Thus, the cancellation of perspective is not merely a refusal of illusion: it becomes a framework that welcomes the unexpected without sinking into randomness. The surface acts as a grid channeling imbalance. The painting is not a space to enter, but a field where one confronts the coexistence of signs.

The absence of depth as structuring principle

In all his series, René Mayer maintains this coherence: no perspective, no optical escape. Whether in “Boxes”, “Moving Earth”, or “Imperceptible Shift”, the viewer remains face to face with the surface. This choice is not formalism: it displaces vision.

By cancelling perspective, René Mayer rejects the implicit hierarchy that places a sovereign point of view above all. Each form exists for itself, in lateral balance. The painting becomes an active field, not an illusionistic stage. This austere frontality generates a particular intensity: the eye does not enter a painted world; it confronts a structure.

Conclusion – art without escape

For René Mayer, the cancellation of perspective is neither stylistic effect nor modernist citation. It is both a visual and critical strategy. It forbids the viewer from taking refuge in depth and compels confrontation with the surface. The painting ceases to be window; it becomes wall: a taut, saturated, active wall.

In this refusal of illusion, every element gains weight and value. Nothing is relegated to the background: everything exists on the same level. This choice underpins the intensity of René Mayer’s work, where the gaze does not drift into space but clings to the surface — where true pictorial dynamics unfold.

From ALICIA: This is just too negative. Remove.