The Origins of a Passion

René Mayer (1947) was born and raised in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, in the Basel region. Basel, Switzerland’s third-largest city, borders Germany and France along the great Rhine River. Industrious and studious, commercial, and flourishing, the city is known for its tolerance. René Mayer’s cosmopolitan spirit therefore has deep roots. But that’s not all!

This unique geographical setting — at the intersection of three cultures — deeply influenced his worldview. Growing up in a city that hosts European institutions, international fairs, and where multiple languages coexist daily, René Mayer was immersed early on in an open environment where diversity is seen as a strength. Regular visits to museums and exhibitions just across the borders in Germany and France were part of his everyday life. This multicultural foundation — both rooted and outward-looking — helped shape in him a curious sensibility, attentive to nuance and naturally drawn to encounter and exchange.

René Mayer is one of those incorrigible optimists who believe that obstacles are made to be overcome. Whatever he takes on, he develops with passion and sees through with determination. From a very young age, he already showed a strong desire for autonomy and a firm will to succeed. Case in point: when he was still a primary school child, he successfully set himself up as a dog walker — sometimes handling as many as six at once! — to supplement the modest pocket money his parents gave him. Later, as a teenager, he led the scout group he had been entrusted with from last to first place in the Basel rankings — in record time. In short, no challenge ever puts him off — they all energize him. Still today — and no doubt tomorrow as well!

This taste for challenge, rooted in childhood, has never worn off. Every stage, every project, every obstacle encountered has been an opportunity for him to learn something new, to test his limits, to refine his ability to solve problems through action. His temperament is not one of waiting or complaining, but of momentum and perseverance. He doesn’t pursue success for its outward signs, but as a sign of coherence between effort, method, and vision. Even as a child, he understood that self-confidence is built through repeated action, and that initiative, however modest, is the key to any kind of growth. This mindset never left him — it only grew stronger over the years, becoming one of the fundamental engines of his life’s path.

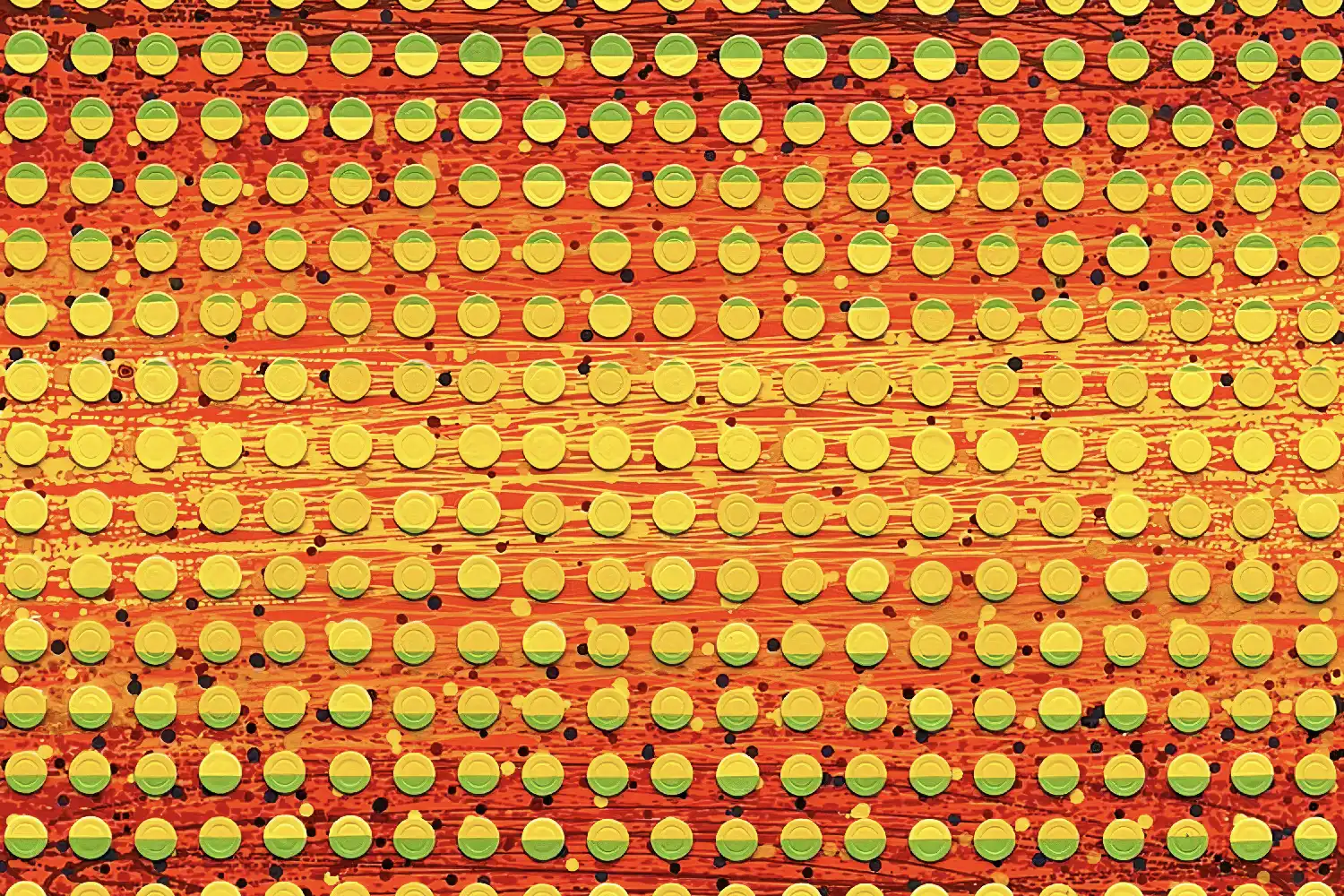

This early entrepreneurial spirit developed over the years and culminated in the founding, in the 1970s, of a soon-to-be flourishing commercial enterprise dedicated to tableware — but that’s another story. Having achieved the financial independence he had aimed for through this company, René Mayer was able to devote himself more freely than his artist friends — whose existential anxieties and struggles he fully understood — to his work in painting and sculpture.

This company, created at a time when lifestyle and design were beginning to occupy a growing place in daily life, found an audience receptive to quality, functional beauty, and understated aesthetics. It allowed him to combine commercial rigor with attention to detail — two qualities he has always cultivated. This economic success gave him not only the financial means to free himself from material constraints, but also the mental freedom to explore his artistic vocation without compromise. He has never opposed business and creation: to him, both stem from the same inner drive for coherence, vision, and precision. This journey enabled him to become a full-fledged artist — not through a break with his previous life, but through continuity with his pursuit of accuracy and meaning. These are the specific features that make René Mayer’s biography so ambivalent.

Jack-of-all-trades with a rebel streak

The corollary — and the prerequisite — of this boundless and uninterrupted activity is René Mayer’s innate, near-insatiable curiosity. For him, nothing is inherently uninteresting especially not in the cultural domain. He became passionate about art in all its forms at an early age, discovering for instance with amazement and enthusiasm the unconventional organic architecture of the Goetheanum by Rudolf Steiner and the surrounding buildings in Dornach. The cultural rupture implied and symbolized by Steiner’s architectural concepts (though he does not share Steiner’s anthroposophical worldview) fascinated him, as it resonated deeply with a particularly sensitive strand of his character: his rebellious spirit.

René Mayer has never seen this curiosity as a hobby or a mere personality trait. For him, it is a deep inner drive, a vital force pushing him to explore, to understand, to question. It led him to take an interest not only in architecture, but also in the history of forms, in music, philosophy, design, craft techniques, visual poetry, and everything that, in one way or another, engages human beings in a creative or expressive endeavor. It is not a scattered curiosity, but a structuring one — constantly feeding his thoughts, his gestures, and his work. Even when he is simply reading, watching, or listening, it is always with the intent to nourish something broader. The Goetheanum was not merely an aesthetic shock for him — it was a revelation of what formal freedom could look like, of radicality fully embraced, of the possibility of another language. It is also the kind of experience that strengthened his rejection of passive allegiance to any doctrine, trend, or norm.

René Mayer has been a rebel since childhood. But his rebellion has never been theatrical, never a stance of convenience or principle. When he revolts, it is out of conviction — because he is confronted with something unjust, abusive, arbitrary, absurd, or iniquitous. And when that happens, he fights for others as much as for himself, regardless of the cost. This libertarian mindset, this desire to break with prevailing conformism, is what led him early on to become an artist — much to the dismay of his parents, who would have preferred to see him follow a conventional bourgeois career path!

His refusal of pre-established paths emerged very early on as an imperative need for truth. To him, being a rebel is not about shocking others, but about remaining true to what one feels is profoundly right. It implies an ability to resist social pressure, to stand by one’s choices even when they disturb others. As a teenager, René Mayer already showed a kind of inner intransigence: he could not accept living a life dictated by external expectations. This need for coherence, freedom, and authenticity is what naturally led him to art — not out of a taste for originality, but because he sensed that only there, and nowhere else, would he be able to breathe at his own pace, think freely, and build a body of work in his own image. This choice was not always understood, or even accepted by those around him — but he held firm, without hesitation, because he knew he had no other path to follow.

A Product of His Region

René Mayer is truly a product of his region. His eclecticism and liberalism are deeply rooted in the socio-cultural microcosm of Basel, nourished by the three humanist traditions that shaped the region — German, French, and Swiss — and that over centuries built the great legacy of tolerance allowing major European thinkers, often persecuted and overlooked elsewhere, to flourish on the banks of the Rhine. While the city has long welcomed intellectuals like Erasmus, Johannes Oecolampadius, and Leonhard Euler, it has also been a haven for artists such as Arnold Böcklin, Pipilotti Rist, and Jean Tinguely — ‘Jeannot’, whom René Mayer particularly admires and to whom the city grants near-idolatric devotion… And let’s not forget Basel’s strong ‘alternative’ cultural scene, for which the city and its region have always been fertile ground! In this peculiar world, patrician and wealthy, yet discreet and cultivated — money and culture mix freely and fruitfully. The extraordinary private collections donated or loaned to Basel’s museums attest to this as clearly as the famous annual Art Basel fair, which draws artists and galleries from across the globe to the Rhine city.

To this already rich foundation are added other influences: the presence of pharmaceutical companies open to cultural patronage, proximity to Germany and France fostering academic exchange, and a multidisciplinary university that attracts researchers from around the world. In Basel’s city-center cafés, one often hears Basel dialect, High German, French, and English all mingling together — a constant reminder of a deeply local yet international identity. This confluence of languages and mindsets has shaped René Mayer’s ear and eye: it gave him a taste for hybridity, and the ability to appreciate as much the symbolist canvases of Böcklin as the luminous video projections of Rist or the clanking kinetic sculptures of Tinguely. Citizen-led initiatives find resonance here: self-managed studios, independent music festivals, graphic design collectives — an entire network of alternative spaces thrives in Kleinbasel (Little Basel) and the former port district. In such an environment, ideas circulate fluidly; debate is courteous but sharp; experimentation is encouraged rather than feared. For René Mayer, this dense field of opportunities, models, and counter-models has served as a mental laboratory. It taught him that economic success and artistic rigor are not mutually exclusive; that tradition and the avant-garde are not enemies but potential partners; and that creative freedom thrives best in a strong communal soil.

Living on the outskirts of the canton, René Mayer is a regular at the Fondation Beyeler and the region’s other cultural institutions. When he ‘listens in’ to Mark Rothko’s paintings in the softly dimmed atmosphere of Renzo Piano’s masterfully designed building, when he rediscovers Paul Klee’s late works in a sumptuous retrospective, when he tracks Paul Gauguin’s journey through life and painting, following the artist’s geographical and artistic wanderings, or when he feels the breeze rustle through the trees wrapped by Christo and Jeanne-Claude in the park at the Fondation — he is never sated, never dulled, never blasé.

Each visit is a ritual: he arrives early, takes his time wandering through the galleries at a slow pace, and commits his impressions to memory. He studies each work he deems essential with care and focus: the pigments, the technique — then lingers in the museum bookstore to leaf through the latest catalogues. This method, systematic but never mechanical, directly feeds his own work: Rothko’s chromatic palette sharpens his sensitivity to nuance, Klee’s graphic rigor deepens his love of structure, and the gestural freedom of Gauguin or the environmental boldness of Christo constantly expand his artistic horizon. In Basel, beyond the Fondation Beyeler, he also frequents the Kunstmuseum, the Schaulager, and independent galleries, convinced that the dialogue between major institutions and emerging scenes sustains a vital creative energy. When traveling abroad, he seizes every opportunity to visit key galleries along the way — with the same meticulous attention. This steady curiosity, combined with an undiminished capacity for wonder, makes every exhibition not merely a diversion, but a moment of active study, a space for silent listening in which his deep relationship with art — and with life itself — continually unfolds.

Exuberance and Rationality Underpin the Biography of René Mayer

We’ve already touched on how the organic architecture of the Goetheanum appealed to René Mayer. But his affinity for biomorphic forms is only one side of his artistic sensitivity. The other is his predilection for simplicity and minimalism — ideals promoted from the 1920s onward by an academy that would become world-renowned: the Bauhaus, founded by Walter Gropius in 1919 in Weimar, relocated in 1925 to Dessau, and dismantled in 1933 in Berlin-Steglitz under pressure from the Nazi authorities. In this institution, teaching and research initially focused on restoring value to craftsmanship in art. Then came a broader reflection on the simplification of the forms of everyday consumer goods. Whether salt shakers, teapots, bedside lamps, wallpaper, or furniture — especially chairs and sofas — the decorative style inherited from the previous century was fundamentally called into question. For the ‘masters’ (as the Bauhaus instructors were called), the simplification of form had a dual purpose: industrial (to produce objects rationally) and aesthetic (to create beautiful ones). This reflection culminated in the concept of ‘less is more’, that is, the rejection of superfluous ornament — a concept that also became the motto of German-American architect and designer Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, one of the most influential Bauhaus figures. Mies played a pivotal role in spreading the Bauhaus spirit worldwide. His famous German Pavilion at the 1929 Barcelona World’s Fair, designed with Lilly Reich, along with the ‘Barcelona’ chair created for that pavilion, remain among his most iconic achievements.

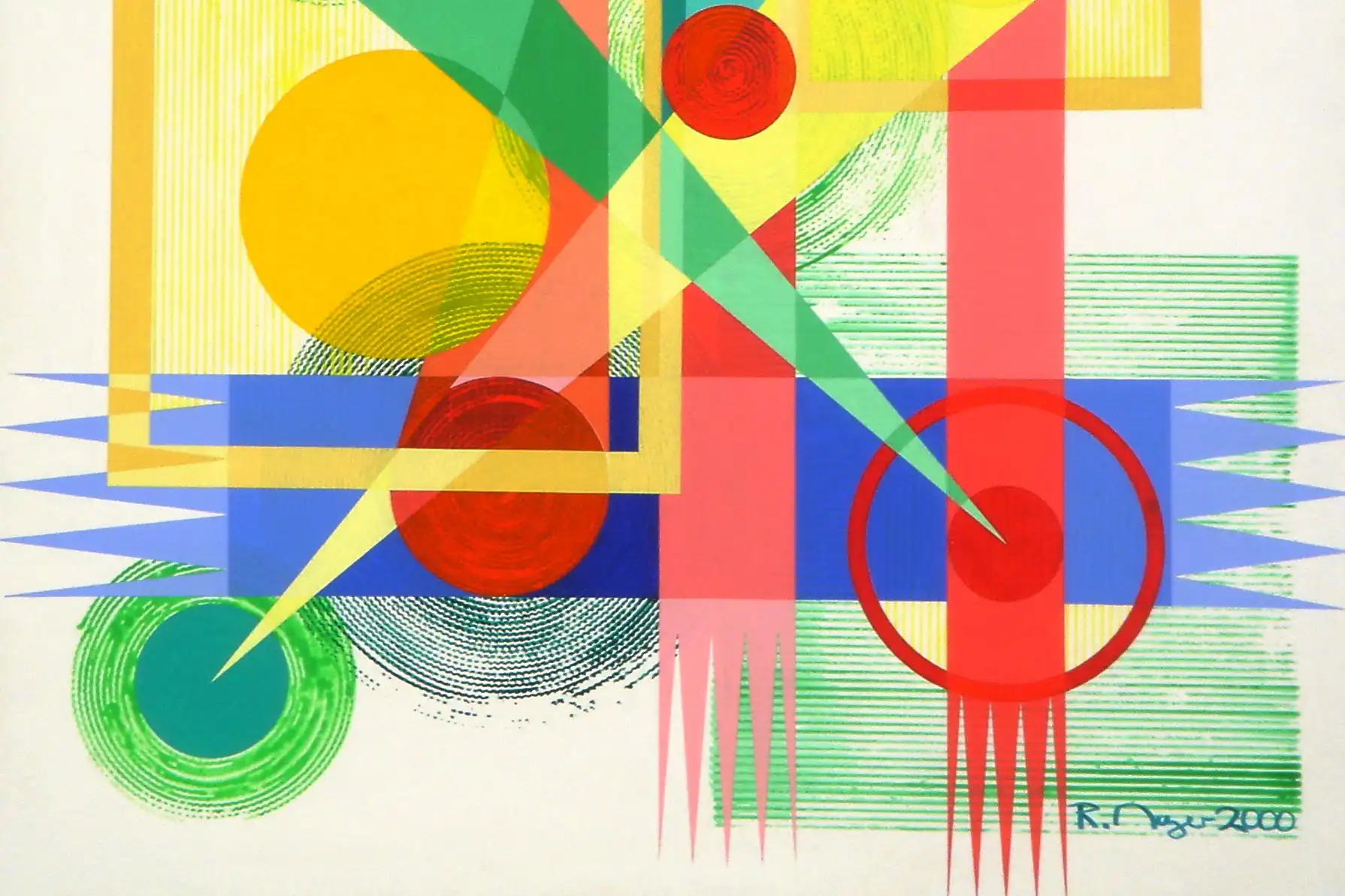

René Mayer, in exploring these two extremes — organic abundance on the one hand, geometric rigor on the other ‘ does not seek to resolve a contradiction but rather to inhabit a fertile tension. He doesn’t choose one over the other: he embraces both as complementary resources, parallel languages capable of fulfilling different expressive needs. This dialogue between opposites nourishes his own artistic practice: at times, he is guided by the intuition of curves, flow, and gestural freedom inherited from organic architecture; at other times, he favors the clarity of rational design and the efficiency of simple structures. For him, it’s not so much the form that matters as the coherence between intention and realization.

It’s no coincidence that Bauhaus objects and the mystical impulse of the Goetheanum coexist in his imagination. They embody two different ways of connecting art to the real world: one through the power of symbolism and the spirituality of forms; the other through functional intelligence and the beauty of utility. René Mayer stands at the crossroads of these two legacies. He admires the radical vision of figures like Gropius and Steiner, who rethought not only what one creates, but how and why one creates it. This visionary rigor is something he strives to incorporate into his own approach: crafting works that speak both to the senses and the intellect, that engage the eye but also stimulate reflection — and that, beneath their apparent simplicity, carry the imprint of a demanding and sincere inquiry.

Returning to the two conceptual poles that guide René Mayer, one might hastily assume that he shows a disconcerting ambivalence by embracing two seemingly incompatible doctrines. But this contradiction is only superficial. Or rather, it pertains only to style. The minimalist aesthetic of the Bauhaus clearly contrasts — or more precisely, forms a counterpoint — with the exuberant biomorphic design of organic architecture. The real question is: what connects the world of the Bauhaus with that of the Goetheanum? The answer is strikingly clear: the shared commitment to craftsmanship. Organic architecture, which seeks to evolve in harmony with nature — as advocated by Frank Lloyd Wright — naturally favors materials like brick, wood, and stone, thereby supporting the crafts that shape them. Both Steiner (who built the Goetheanum in concrete, let’s not forget!) and Gropius were deeply aware of the importance of manual know-how. Steiner even stated in his teaching principles that the goal of school manual work (what we now call ‘visual arts’) was not simply to develop technical skill but to result in the creation of useful, usable objects.

This shared vision is far from anecdotal — it lies at the very heart of what René Mayer sees as the foundation of his practice. For him, it is not a superficial historical overlap between two admired schools of thought, but a deep anchoring in a particular idea of gesture, material, and utility. Far from seeking a formal synthesis between stylistic languages, he recognizes that the shared artisanal ethic gives objects, forms, and creative processes an inner density — an authenticity that transcends appearances. He is less concerned with what things show than with what they reveal: their fabrication, their genesis, their relationship to the world. Matter — whether natural or industrial — becomes expressive when it is shaped with care, rigor, and attentiveness. This, in his view, is what connects the clean lines of the ‘Barcelona’ chair with the unpredictable curves of a Goetheanum column: the capacity to embody thought in form, without embellishment or evasion. The profound link between these two universes lies not in aesthetics but in process — in the value placed on handiwork, on the concrete intelligence of materials, on the relationship between humans and what they shape. René Mayer sees in this a way of inhabiting the world with accuracy — nothing more, nothing less.

So, an acute awareness of the vital importance — ‘vital’ in the sense of ‘essential to life’ — of craftsmanship is the guiding thread in René Mayer’s life. When he says that, deep down, he is a craftsman, he clearly (if implicitly) emphasizes the notion of life: the heart is where not only the pulse of biological life beats, but also that of emotional life. Over the years and through his artistic experiments, René Mayer has come to understand ever more deeply the necessity of the creative act and the importance of making something with one’s own hands. It is in the honesty and humility of this approach’which runs throughout his biography — that the spark is born which gives his works the personality, legitimacy, and vitality that mass-produced items from a factory on the other side of the world can never possess.

That, for him, is the true meaning of “creation”: not simply bringing a form into being, but entering into a relationship with the material, engaging in dialogue with it, understanding and listening to it. This dialogue — sometimes slow, sometimes demanding — requires attention to detail, presence in the moment, and a quality of gesture that only hands-on experience can provide. That is why the creative act is, to him, the exact opposite of industrial production: it is not standardized, it does not seek uniformity, it bears the marks of the individual — the mood of the day, the body’s tension. René Mayer sees in this a kind of truth: the truth of who we are, confronted with what we do. He does not claim the status of an artist locked away in an ivory tower, but that of a craftsman who returns to his workbench each day with seriousness, honesty, and commitment. And it is this constancy — this fidelity to the work — that gives the objects born of his hands a kind of life, a tangible uniqueness, a presence that resists all forms of replication.

Conclusion

Rather than looking to family background, the origins of René Mayer’s artistic passion must be found in his rebellious temperament, in tune with the profound societal upheavals of the 1960s and 70s, and in the climate these changes fostered within the cultural microcosm of Basel that he was immersed in. His parents belonged to the educated bourgeoisie, but were not engaged in the arts at that time. It was only much later that René Mayer’s stepfather (his mother’s second husband) took up painting and sculpture — without, however, making it a career.

This disconnect between a cultivated yet artistically unexpressive family environment and a deeply creative personal sensibility likely reinforced René Mayer’s need to explore untrodden paths on his own. The intellectual climate of that era — marked by protest movements, the rise of countercultures, the questioning of established hierarchies, and the valorization of individual expression — offered a particularly fertile ground for such a sensibility. Basel, with its vibrant cultural scene, cross-border openness, and multiplicity of influences, acted as a catalyst. It was in this transforming space that René Mayer began to define his own visual language, on the margins of dominant models.

If one were to identify a family figure who may have exerted — even belatedly — some form of artistic emulation, it would most likely be that self-taught stepfather. But for René Mayer, the impulse comes from elsewhere: it is rooted in an inner necessity, a vital tension between interiority and form, between a perception of the world and the need to give it expression.